Detention Snapshot: Spring 2022

This digest contains a summary of documented human rights abuses that occurred in ICE detention throughout the months of April and May 2022, in addition to examples of how immigration detention affects immigrant communities. Abuses described in this report were primarily reported to Freedom for Immigrants’ (FFI) free and unmonitored National Immigration Detention Hotline, which receives roughly 600 calls per week, and by community-based detention visitation groups within FFI’s National Visitation Network. An important group of advocates are individuals in detention (“detained advocates”), who courageously communicate with FFI and other groups to report the unfair and inhumane treatment they face, despite the risk of retaliation and further abuse by ICE.

Abuses documented in this report include incidents of sexual harassment and assault, anti-Black racism, and physical violence, in addition to examples of detained advocates’ internal organizing and resistance. These incidents offer a window into the realities of immigration detention and ICE’s abusive practices across its detention system.

Sexual Harassment

Guards engaged in inappropriate behavior and sexual abuse against detained advocates. Specifically, detained advocates reported being discredited, neglected, and threatened upon disclosing the incidents. Indicative of the systemic and pervasive sexual abuse found throughout ICE's detention system, recently reported instances of sexual assault include strip searches and nonconsensual, violent physical groping. In several incidents, people reported being physically restrained and video recorded while being stripped searched. Per ICE’s own standards, strip searches are only to be used under exceptional circumstances.1 Additionally, this May, researchers with the University of Washington Center for Human Rights released a report tracing over 60 sexual harassment and assault incidents at the Northwestern Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington.2 The researchers found that the facility was not implementing any of the standards to which they are bound, including the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) and ICE’s own standards, concluding that more policies cannot fix endemic issues in the detention system.

Otay Mesa Detention Center (San Diego, CA): Multiple people reported being sexually harassed by a facility officer, who inappropriately touched one individual and engaged in sexual voyeurism. The facility case manager discredited the advocates who reported the abuse and threatened them with solitary confinement. While the officer was ultimately removed from the detained advocates’ unit, they remain concerned about harassment occurring in other units. In addition to reporting the incidents to the staff, detained people filed a PREA report, but they were told it was “lost.”

Denver Contract Detention Facility (Denver, CO): A Black detained advocate was sent to the suicide guard for requesting to be moved to a different unit. He protested, as he wasn’t suicidal. However, the guards forced him into a room, ordered him to take off his clothes, and beat him. The guards then handcuffed him and took pictures of him while still naked. The detained advocate now needs a wheelchair for mobility, since the guards broke one of his knees in the incident.

In another example of systemic abuse, again at Otay, a detained advocate was interviewed on an incident as part of an investigation about a reported sexual assault he suffered by a facility officer while the offending officer was sitting in the room. The investigator refused to remove the officer or to give a copy of the interview to the detained advocate.

Anti-Black Racism

Black immigrants continue to report racially motivated verbal and physical abuse and are disproportionately punished by ICE officers and facility staff.3 Furthermore, detained advocates report that Deportation Officers discriminate against Black immigrants by using their discretion to only release white immigrants. Detained advocates also describe how facility staff and ICE officials are more likely to escalate to violence instead of using alternative strategies against Black immigrants compared to other immigrants. These instances of physical violence fit within a long pattern of anti-Black racism that Black immigrants experience within ICE custody, a practice which ICE leadership has effectively condoned.4

Aurora Contract Detention Facility (Aurora, CO): A Black immigrant reported being assaulted by a facility officer during a cell search. The detained advocate reports that the officer used racial expletives and pepper spray against him. Instead of de-escalating the situation, two other officers tackled the Black immigrant and joined in using force. “At some point while the officers held me down, one of the officers lifted my dreadlock from my face and pepper sprayed me again.”5

Krome North Service Processing Center

Krome North Service Processing Center (Miami, FL): Facility staff denied multiple requests for adequate and life-saving medical care for a detained advocate. The detained advocate noted that non-Black detained immigrants get support faster than Black immigrants, and that Black immigrants are treated more “heavy-handed.” In a separate incident, a detained advocate reported physical violence against a Black immigrant, who was body-slammed, choked, and had his limbs forcefully pulled away from his body by more than 30 guards. One of the assaulting officers had previously been reported as verbally abusing Black immigrants. A guard explicitly told the detained advocate not to report the physical assault he had witnessed and to inform Spanish speakers not to report the incident.

Physical Violence

Multiple individuals in detention reported being physically assaulted by facility staff and ICE officers. Physical violence by ICE officials and guards is common throughout the detention system, and this type of assault usually occurs when multiple guards retaliate after someone speaks up for their rights or after a slight disturbance or inconvenience when people are transported between cells. Furthermore, detained advocates report very violent beatings as common occurrences that often result in detained people losing their mobility.

Krome North Service Processing Center (Miami, FL): There was a shakedown of a unit conducted by facility staff. Multiple people reported unnecessary and excessive use of force. In one instance, an officer threatened a detained person with pepper spray, slammed his face against the glass, and “roughed him up” while throwing him into solitary confinement, just because the detained person asked the guards to be careful with his legal documents. The same individual had been sent to the hospital months ago after being physically assaulted by facility staff. Another detained person shared that he believes this is a form of retaliation against the complaints that he and other advocates have recently filed.

Krome North Service Processing Center (Miami, FL): A detained advocate witnessed a facility officer violently beating another detained man for not “moving out of the way” fast enough. Per the detained advocate, the assaulted man is now using a cane. Immediately after the attack, other detained people protested the violence. The detained advocate attempted to de-escalate the situation, while the assaulting officer escalated by insulting the detained people. Shortly after being verbally threatened, the assaulting officer hit the detained advocate and placed him in solitary confinement. In a separate incident, an advocate witnessed a detained person covered in blankets after becoming unconscious due to a severe beating by guards.

Internal Resistance

Detained advocates use a variety of tactics to organize and resist ICE’s mistreatment and unjust detention. Mass hunger strikes, solidarity actions, petitions, media advocacy, and political advocacy are just a few ways people in detention fight for their liberty and dignity. Some of these efforts are in protest of abuses and detention conditions, while others are examples of mutual care.

Krome North Service Processing Center (Miami, FL): Roughly 60 detained immigrants went on hunger strike to protest the abuse at Krome described throughout this digest. ICE officers cuffed the individuals and put them in solitary confinement for two weeks to retaliate against their organizing efforts. The organizers still succeeded in sharing their stories with attorneys and community members supporting in solidarity.

Northwest Detention Center (Tacoma, WA): Detained advocates engaged in two hunger strikes, which ended after some of their demands were finally met. Some demands included getting access to clean clothes, improved food portions, and more on-site ICE officers to handle immigration dockets. Some of these conditions only improved in the unit where detained advocates hunger striked.

Baker County Sheriff's Office (Macclenny, FL): Over 100 detained advocates joined a May hunger strike to demand appropriate medical care, and for ICE to address ongoing issues including inappropriate COVID-19 responses, use of force, racism, and bug-infested food. The detained advocates are also protesting a recent death in the facility—the second in only two years. Mirroring past retaliation, facility staff cut off access to water, including drinking water. The detained advocates were forced to stop their hunger strike to resume access to water, as conditions became unhygienic and dangerous.

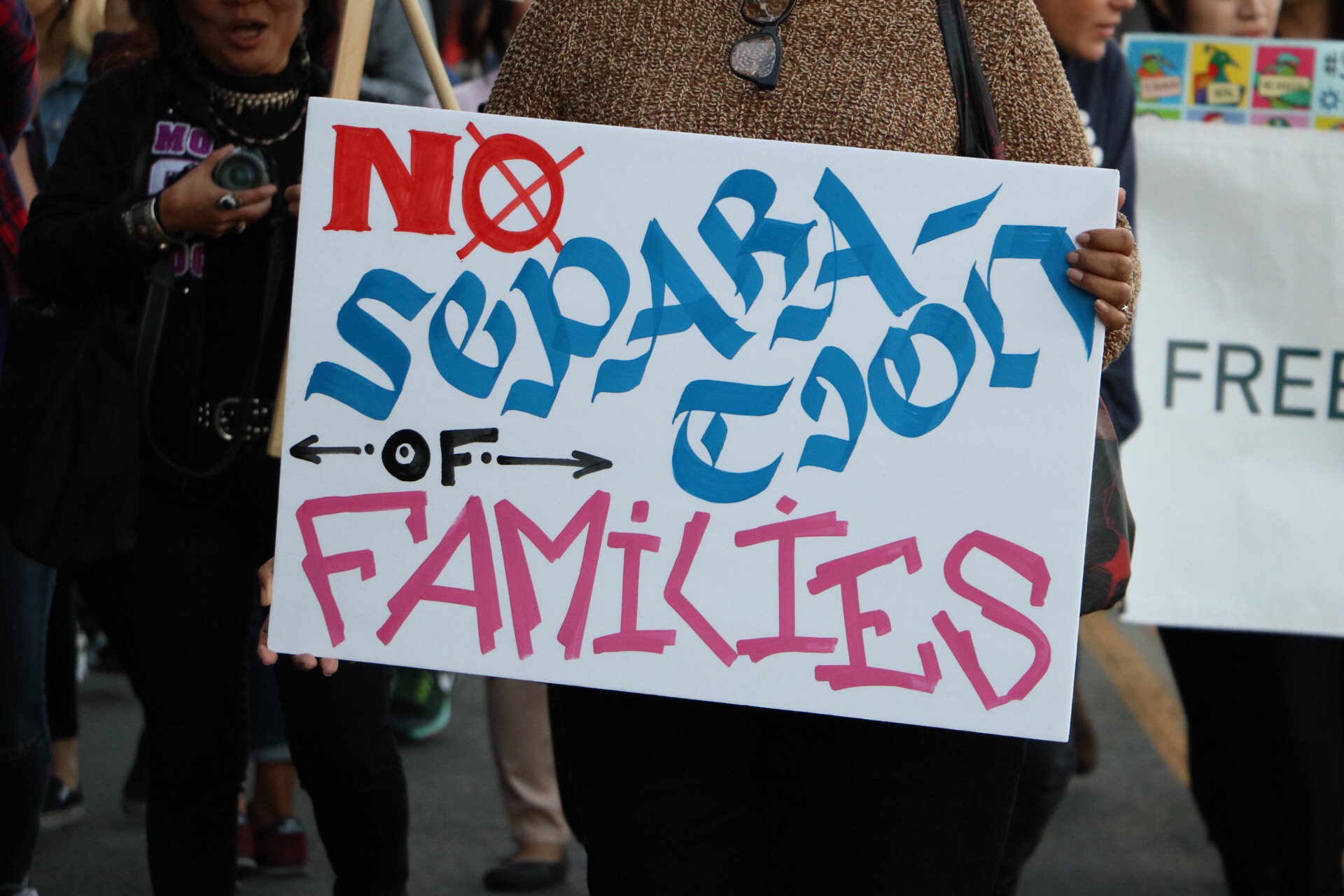

Trauma in Immigrant Communities

Immigration detention directly and disproportionately affects communities of color across the United States.

When individuals are detained, they are ripped away from communities, loved ones, and the workforce. The trauma from these distressing events ripples across entire communities and leads to many challenges within immigrant communities, which are most often composed of people of color.

Excerpt from Family Separation in Immigration Goes Well Beyond the Border, by FFI’s Policy Director Andrea Carcamo in her former capacity as Senior Policy Counsel at the Center for Victims of Torture:

“In fiscal year 2019, the average daily number of individuals in immigration detention was 50,165, and a total of 510,854 individuals were detained. Children have been left abandoned at school because their parents were detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) during the day. Daily, asylum seekers and other individuals who have been contributing to our community for years – or even decades – are sent to a cell while their children are left wondering if the last time they saw their parents was truly the last. Some might be deported and others might spend months, or even years, in detention while they seek immigration relief.”

Surprising Facts About Detention

Highlights

ICE announces updated phased return to social visitation at detention facilities: FFI and more than 20 local detention visitation groups and immigrants rights organizations led a year-long campaign to reinstate visitation, which succeeded on May 11, 2022. While this announcement is welcome news, FFI will continue to closely monitor detention centers’ compliance with the updated guidance. “The realization that I will be able to hug my daughter brings me so much joy,” said Fidel Garcia, who is currently detained at Golden State Annex in McFarland, California, in a press release reacting to the updated guidance.

Learn more about FFI’s monitoring and investigations work here, and FFI’s policy work here.

Citations

Office of the Inspector General “Concerns about ICE Detainee Treatment and Care at Four Detention Facilities” (June 2019) available at https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2019-06/OIG-19-47-Jun19.pdf

University of Washington Center for Human Rights, “Calls to nowhere: Reports of sexual abuse and assault go unanswered at the NWDC” (May 2022) available at: https://jsis.washington.edu/humanrights/2022/05/16/nwdc-assault-abuse-reporting/

Freedom for Immigrants, “Addressing Anti-Black Racism in Immigration Detention” (2021) available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a33042eb078691c386e7bce/t/620fd0713b8bf853d06100cc/1645203571174/FinalVersion.Addressing+Anti+Black+Racism.+Report.pdf

Black Alliance for Just Immigration and NYU School of Law Immigrant Rights Clinic, “The State of Black Immigrants” (September 2016), available at: http://baji.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/sobi-fullreport-jan22.pdf

American Immigration Council, Immigrant Justice Idaho, and Immigration Equality. “Council Files Complaint Against ICE for Racial Discrimination and Excessive Use of Force in Colorado Facility.” March 24, 2022. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/council-files-complaint-against-ice-racial-discrimination-and-excessive-use-force-colorado