Why Freedom for Immigrants believes in abolishing immigration detention

LEGACIES OF SLAVERY AND COLONIALISM

Freedom for Immigrants is working toward the abolition of immigration detention.

Abolitionist resistance draws from a legacy of Black- and Indigenous-led movements in the United States and around the world that fought for liberation against slave, colonial and neocolonial societies.

Today, slavery and colonialism are still alive in the form of our global incarceration systems, which privilege profit over people.

Accordingly, we continue to see fierce resistance to modern-day oppressive institutions like prisons that seek to uphold a racial and capitalist order. Abolitionist movements not only assert that abolition is desirable, but that it is also possible, even likely in the long term (and the sooner the better).

Immigration detention is a part of this mass incarceration system, and we stand with allied organizations fighting for the abolition of all prisons and jails.

HISTORY OF U.S. INCARCERATION

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world and imprisons 2.2 million people on any given day — a 500% increase over the last 40 years.

The United States also has the largest immigration detention system in the world, detaining 400,000 people each year.

Prisons and jails did not evolve naturally in response to dangerous conditions or crime. Instead, they were designed by political and corporate interests to extract profit from and suppress the power of marginalized communities and peoples.

After stealing land from Native people, settlers in the United States passed laws to criminalize and incarcerate the very people they had dispossessed. This happened all across the United States, from California to New England, prior to the ending of slavery. For example, cities passed laws that made it a crime for people not to be gainfully employed, allowing settlers to jail Native people and force them to work building roads or sell them to settlers for forced labor.

After slavery ended, more and more prisons were built and used to ensure that Black people could not escape social and economic discipline.

While the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution may have abolished slavery or involuntary servitude in 1865, it also created an exception for people convicted of crimes. This loophole was immediately exploited.

Prisons, particularly in the South, would lease large numbers of convicts — mostly Black people arrested under the Black Codes — to plantation and factory owners. In fact, many prisons were erected on abandoned plantation lands and convict laborers were forced to cultivate cotton for no pay.

This convict leasing system paved the way for the symbiotic relationship between state-sanctioned incarceration and private enterprise that is the status quo today.

In truth, the rise of immigrant prisons and jails throughout the world in the 1980s and the 1990s can be traced back to the formation of the private prison industry in the United States. Compared to the 1800's when privatization of prisons mostly involved individuals and local business, the 1980s gave rise to national and international corporations focused solely on incarceration. The first private prison company was formed in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1983, and expanded internationally in 1990.

This relationship between state incarceration and private enterprise survives today. And this relationship is supported by capitalistic profit motives that drive urban gentrification, rural economic and ecological blight, and land speculation in both urban and rural areas.

These outcomes in turn exacerbate homelessness, foreclosures, lease cancellations, and the loss of jobs through forced relocation. Many of these people are then imprisoned through a homelessness-to-prison pipeline.

WHITE SUPREMACY & THE START OF IMMIGRATION DETENTION

One of the uncanny features of immigration detention in the United States is how young and how old it is. Until fairly recently, immigration detention didn’t exist in its current scale, and yet its existence today seems predetermined by this country’s long, disturbing past.

As under slavery and as today, people of color were abducted from their communities and forced to work for the profits of a ruling class steeped in the ideology and practice of white supremacy.

As under slavery and as today, poor rural white communities were kept in thrall to a social order that exploited them through what the great historian and social activist W.E.B. Du Bois called “a psychological wage” of whiteness. This psychological wage — as opposed to a financial wage — provided white people with the satisfaction of a higher standard of living than their Black countrymen as well as access to a modicum of political power and social prestige.

Like the institutions of slavery and colonialism, immigration detention in the United States grew out of a white supremacist model of exploitation and disappearance.

THE FIRST GROUP OF PEOPLE TO BE TARGETED

The first Immigration Act in the United States, passed in 1790, was explicitly racist, allowing U.S. citizenship to be granted only to “free white persons” of “good moral character.”

Although citizenship was regulated, migration was not as closely monitored until 1882, when immigration detention soon followed.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in order to prohibit Chinese laborers from entering the United States for 10 years.

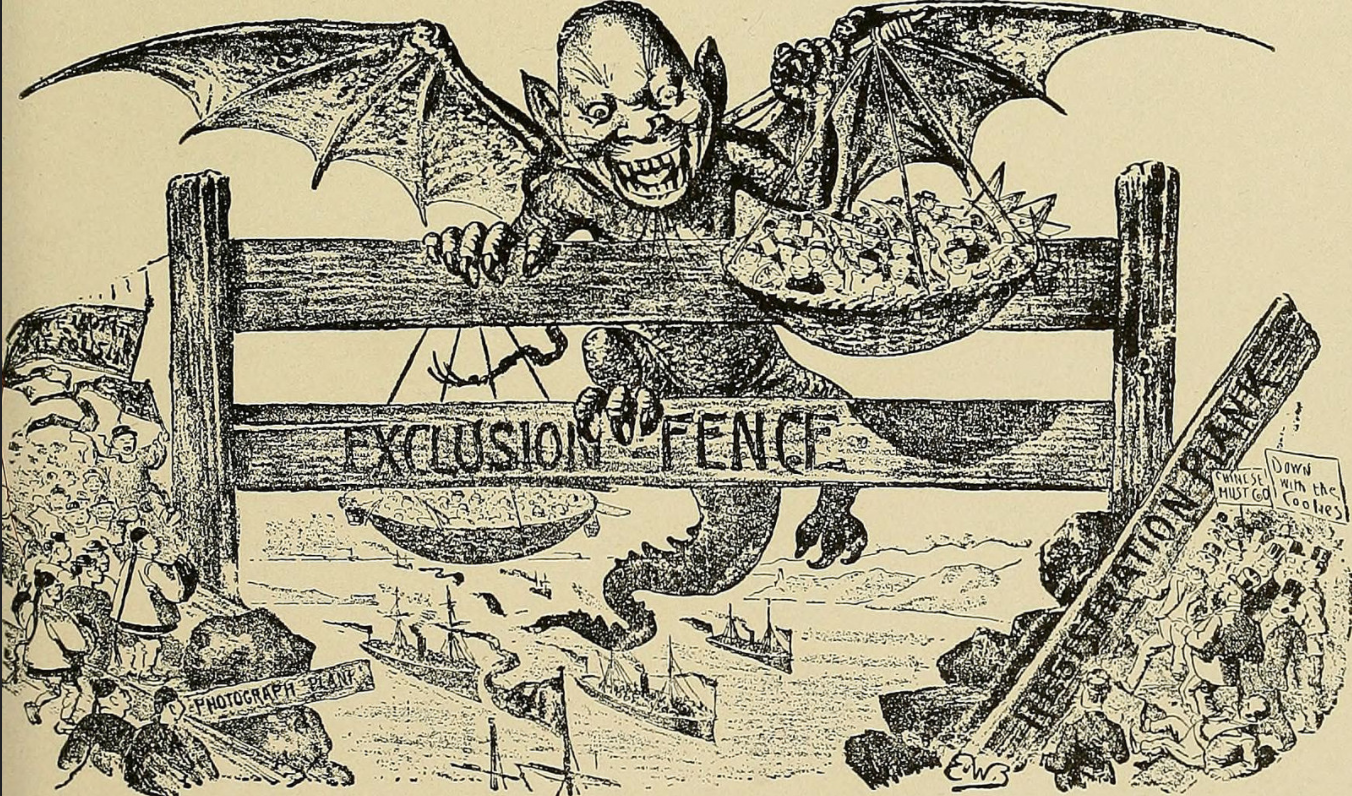

This xenophobic illustration was published in the "The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp" in an effort to dehumanize Chinese immigrants. Image can be found in "The History of the Nineteenth Century in Caricature" via Internet Archive Book Images.

After the law expired, Congress passed the Geary Act of 1892, requiring all Chinese laborers to register with the government or be subject to arrest, one-year imprisonment, and then deportation.

Together, the laws were aimed at expelling Chinese immigrants from settler-claimed lands. In the eyes of the lawmakers, Chinese immigrants had served their purpose building the nation’s railroad lines from 1858 to 1885.

These laws criminalized immigration for Chinese people, and in 1893, Congress passed its first law requiring the civil detention of any person not entitled to admission. This gave immigration authorities the power of discretion to admit white people, while detaining and deporting people considered non-white.

Over the next 60 years, civil immigration detention began to expand on Ellis Island on the East Coast, Angel Island on the West Coast, in jails, on ships, and other places of confinement across the United States.

Since its inception, immigration detention was designed to jail people of color. For example, just like the Black Codes led to the increase in incarceration of Black people, racial profiling today means that Black immigrants are disproportionately represented in immigration detention. In fact, despite only comprising 5.4% of the undocumented population, 20.3% of immigrants in detention are Black.

GLOBAL INEQUITY & U.S. IMPERIALISM

During the Cold War, intellectuals, politicians, and ordinary people began to think of the world as divided into three camps or “worlds.” “First world” was used to describe societies that developed capitalist forms of exploitation at the expense of the livelihood and autonomy of the “third world” and “second world” economies.

This history of global inequity during the 20th Century is critical in contextualizing and understanding immigration detention, particularly migration patterns.

Migration to the United States and worldwide doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it is deeply affected by economic exploitation, rooted in colonialism and sustained through acts of imperialism, such as war.

From Latin America to the Middle East, millions of people have been forced to migrate from their homelands because of the United States’ military, political, and economic imposition of power abroad. U.S. imperialism has historically, and even today, undermined the freedom of people to choose their own leaders and create their own visions for their futures in their homelands.

This has not only fueled the expansion of immigration detention in the United States, but also around the world. For example, Hong Kong first began detaining immigrants when refugees from Vietnam fled the effects of the Vietnam War.

The recent global explosion of immigration detention, which originated in the U.S. prison-industrial complex, is undeniable.

THE GOAL OF ABOLITION Today

Abolitionists today are entangled in the history of the political and capitalist forces that have allowed jails, prisons, and immigration detention facilities to proliferate in the United States, and around the world.

Abolitionists study the complexity of the relationships that fuel incarceration. For example, the immigration detention system is not just made up of immigrant prisons and jails that confine human beings. The immigration detention system comprises the transnational and domestic prison corporations, guards’ unions, police departments, federal government agencies, and legislatures that make immigration detention possible and profitable. These relationships should be scrutinized, and we should apply the same level of skepticism to them that we apply to other federal government contracts and programs.

Prison abolitionists are not suggesting that we close all prisons tomorrow, but abolitionists recognize that the current system does not prepare people to re-enter society, is an excessive waste of government resources, and is rife with human rights abuses.

In this way, the modern prison system perpetuates the cycle of violence, rather than intervenes on it. Prison abolition, therefore, is as much about compassion as it is about controlled government spending and public safety.

Abolishing prisons and jail in the criminal justice system will require a dual strategy. While we eliminate prisons that perpetuate the cycle of violence, we also must build programs that promote accountability and get at the root cause of past criminal behavior. For example, someone convicted of drug possession does not need decades in prison, she needs drug addiction treatment and a nurturing community of support.

Abolishing immigration detention

Freedom for Immigrants' theory of change has grown out of the abolitionist movement.

Our demand for the eradication of immigration detention recognizes that alternatives that fail to address racism, homophobia, and other structures of oppression will only fuel more oppression. Through our programming, Freedom for Immigrants is proving that community-based alternatives to detention are less expensive than detention and allow families to remain together while their immigration cases are being processed.

We know that the abolition of immigration detention is a pragmatic goal, which with your help can be realistically achieved within this generation.

We encourage you to join us on this journey to abolition.

If you are interested in learning more, check out our reading list about modern-day abolitionist movements.